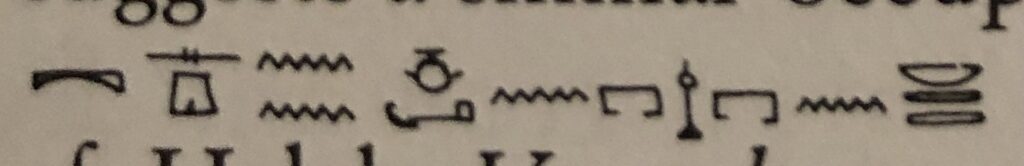

“I shall be anointed with first-class oil and clothed in top linen, and I shall sit on that which makes Maat live, with my back to the back of those gods at the sky’s north—the Imperishable Stars, and I shall not perish; the unpassing ones, and I shall not pass; the unwaning ones, and I shall not wane.”

272a, “Spells For Ascending To The Sky”, The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, James P. Allen

TT 175 is a small (measuring only 1 x 1.60m) anonymous tomb located in el-Khôkha, part of Theban Necropolis on the Nile’s west bank, in Egypt most likely dating back to the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt (16th to 13th BCE).1,2 The tomb appears to be almost finished except for wall ‘H’, however, the first chamber is either missing or perhaps has not been cleared yet.3 The rear wall appears to have contained a stela or statue which is now lost to time and his name was never inscribed in the space left for it in the scenes, thereby removing any clue of the owner’s identity. The painter managed to fit in many scenes such as the conventional banquet scene, agricultural activities, funerary rites, the pilgrimage to Abydos and of particular interest the making of ointments and perfumes. The representation is considered unique; though the man’s occupation of being in charge of unguent industry must have been fairly common.2

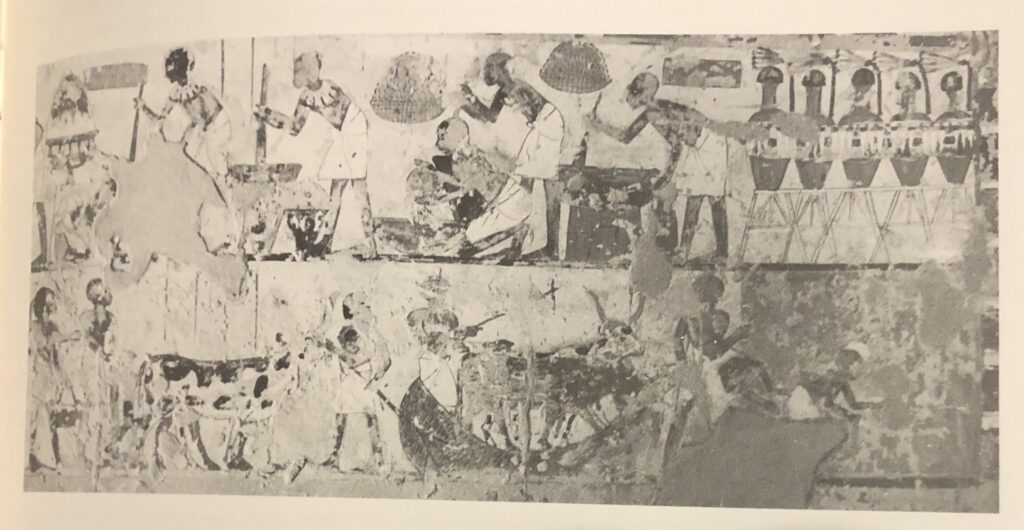

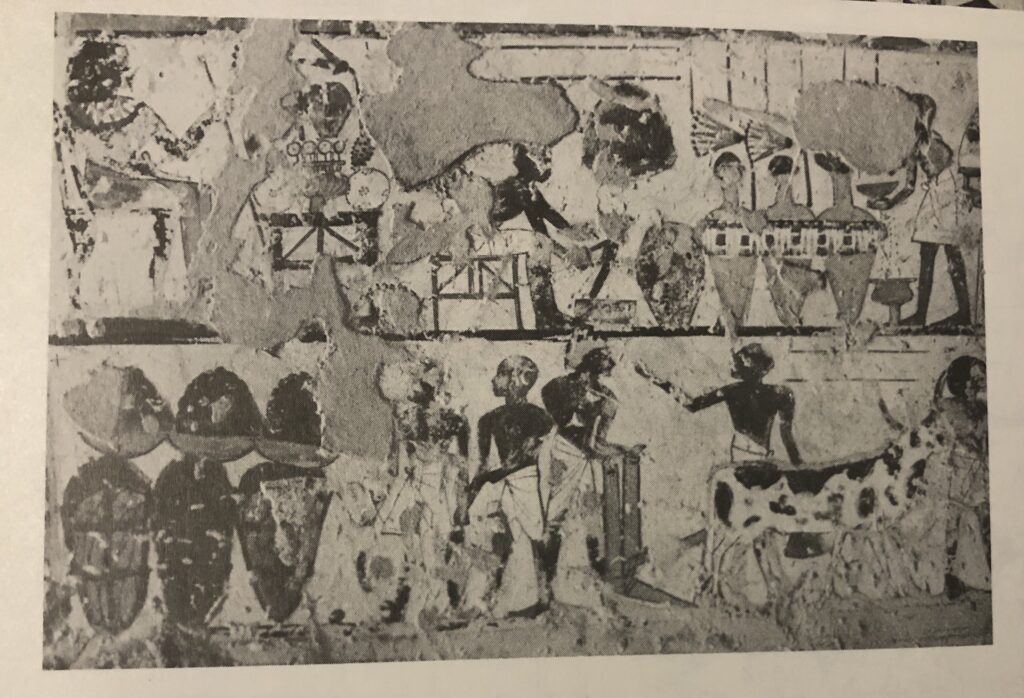

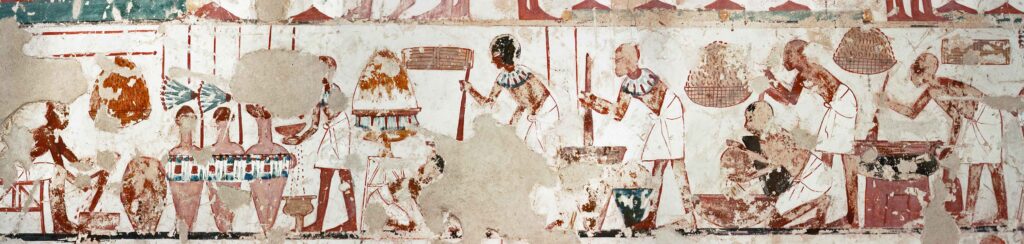

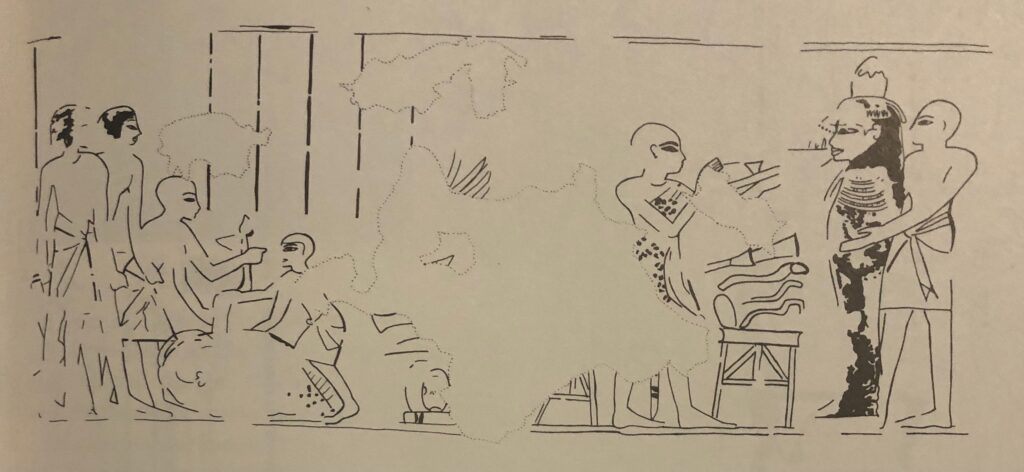

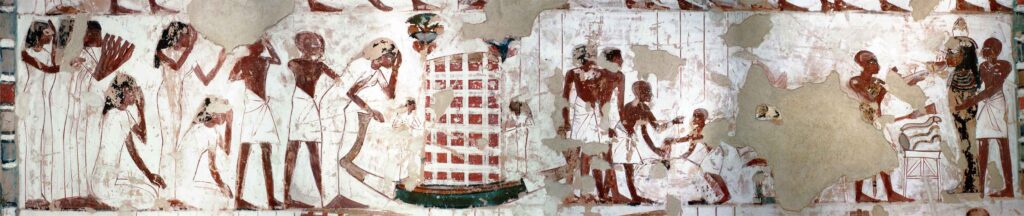

The Lower Right register of the Right Wall depicts what Lise Manniche calls a “Salbeküche”, an ointment/unguent kitchen, which shows the process of making ointments and perfumes. The far-right part of the register shows multiple sealed Egyptian amphorae sitting in pedestals with a blue Egyptian lotus stemming from each one — perhaps indicative of the contents contained therein.

The man to the immediate left stirs a substance, with what appears be a wooden paddle, in a vessel which sits atop what is most likely a tandoor/tannur oven, attested to across the ancient Mediterranean from Egypt to Mesopotamia and even further east in Central Asia.4,5,6 The black coloring on the bottom of the vessel suggests exposure to an open flame that gives off soot.

The next two figures show the processes as according to Dioscorides the seeds were ground carefully in a mill then thrown in baskets to be squeezed for their oils. Ancient Egyptians extracted oil from a multitude of sources such as balanos, bitter almonds, castor, and olives.7,8 Although the picture is difficult to make out, R. J. Forbes believes the third person depicted (going from left to right and not including the tomb owner) or the sixth person starting from the right, is crushing something on a saddle-quern. The person above is said to be mixing the ingredients prepared below in a large bowl.9,10 Given the shape of the “bowl” and the dichromatic “earthenware” and black seen before on the far-right, another round of heating the ointment could be taking place. This is not out of place in the ancient world as this was done many times to refine, reduce the solution, and add ingredients among other procedures.11 “A further [assistant] takes something from one of the three decorated potter jars and throws it onto sieve from which the liquid drops into a vessel below.”9 (page 13)

The person to the left is sitting on a stool working with what appears to be an adze on what may be a wooden plug with the chips following to the ground. According to Lise Manniche, “A wooden bung would be unusual” or perhaps the chips were desired as the use of aromatic woods were used in ointments, perfumes and unguents.12,13 Sheila Ann Byl interprets the use of the adze as shaving down a solidified unguent into various shapes such as balls or cones.14 Given the huge mass of ointment and the laborious nature of such a task, this interpretation would make more sense. With a few more clues, a reasonable assumption of what this substance was used for can be reached. Taking into context the with what Forbes describes and priestly collars, he concludes that they are making a “holy ointment.” Given that this is a tomb whose purpose is a “house of eternity” preparing and providing the owner what they need for the afterlife, Forbes assessment makes sense.15 Looking to the left wall registers, Manniche describes these as the journey of the tomb owner to Abydos.16 On the left wall middle right register the tomb owner is mummified with an unguent cone situated atop the head. These cones have been found in the ancient city of Akhenaten, though the nature of their uses is still being debated.17

The far-left register ends with the tomb owner sitting in a chair holding a cane, indicating his superior position, in front an offering table carrying two loaves, an elaborate metal drinking vessel, a basket of [offerings], and lotus flowers to provide a cover, that is to say the conventional heap of offerings placed in front a seated tomb owner”.12,14

References:

1 Lise Manniche, The Wall Decoration of Three Theban Tombs (TT 75, 175, and 249), Museum Tuscalanum Press, 1988, pp. 31-32.

2 Eighteenth Dynasty:

Egyptian history, Encyclopedia Britannica, (https://www.britannica.com/topic/Eighteenth-Dynasty)

3 Marcel Baud, Les Dessins Ébauché de la Nécropole Thébaine (Au Temps du Nouvel Empire), Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 1935, pp. 190-192.

4 Delwen Samuel, An Archaelogical Study of Baking and Bread in New Kingdom Egypt: Volume 1, 1994, pp. 319-320

5 Francesca Balossi Restelli and Lucia Mori, Bread, baking moulds and related cooking techniques in the Ancient Near East, Food and History, Volume 12, Issue 3, pp. 39-55.

6 Bradley J. Parker, Catherine P. Foster, et al., New Perspectives on Household Archaeology, Cambridge University Press, 2013, pp. 381-396

7 Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, 1-38

8 A. Lucas, Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries (4th Edition, revised by J.R. Harris), Oxford, 1962, pp. 85-90.

9R.J. Forbes, Studies in Ancient Technology. Volume III, Leiden, Brill, 1965, pp. 1-15.

10 AR9457211, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, Great Britain

(https://www.artres.com/archive/-2UN86I5TE7WC.html)

11 Translation by Eduardo A. Escobar, KAR 220 and KAR 222, ORACC Corpus, (http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/glass/corpus)

12 Lise Manniche, The Wall Decoration of Three Theban Tombs (TT 75, 175, and 249), Museum Tuscalanum Press, 1988, pp. 34-38.

13 Sheila Ann Byl, The Essence and Use of Perfume in Ancient Egypt, Master of Arts Thesis for Ancient Near Eastern Studies at the University of South Africa, 2012, pp. 172-176

14 “Tombs in Ancient Egypt”, Australian Museum, (https://australian.museum/learn/cultures/international-collection/ancient-egyptian/tombs-in-ancient-egypt/).

15 Lise Manniche, The Wall Decoration of Three Theban Tombs (TT 75, 175, and 249), Museum Tuscalanum Press, 1988, pp. 38-41.

16 Colin Barras, “These mysterious Egyptian head cones actuall exisited, grave find reveals: But mystery lingers about what they were used for”, Science, 2019, (https://www.science.org/content/article/these-mysterious-egyptian-head-cones-actually-existed-grave-find-reveals).

Note: KAR “Keilschrifttexte aus Assur religiösen Inhalts” (Religious Cuneiform Texts from Assur).

Leave a Reply